My YOUTUBE video of KAMAKURA

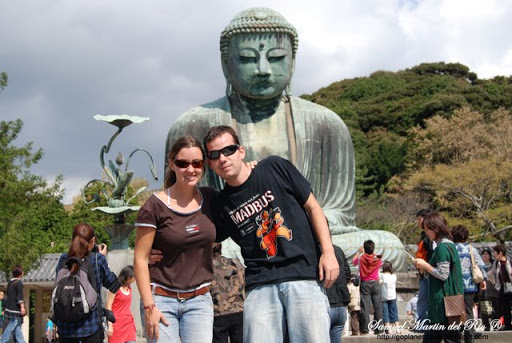

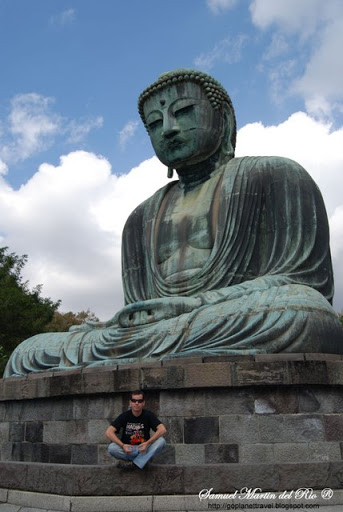

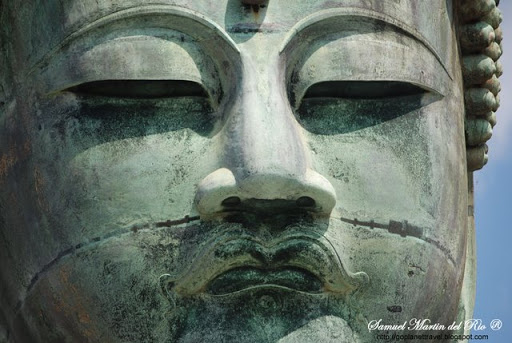

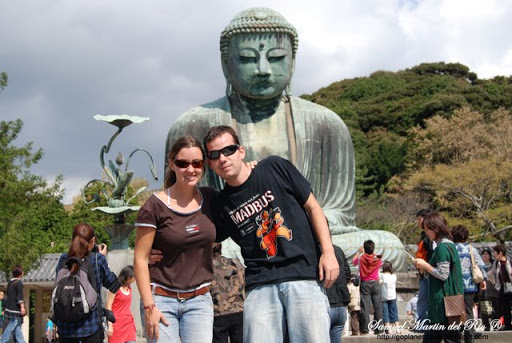

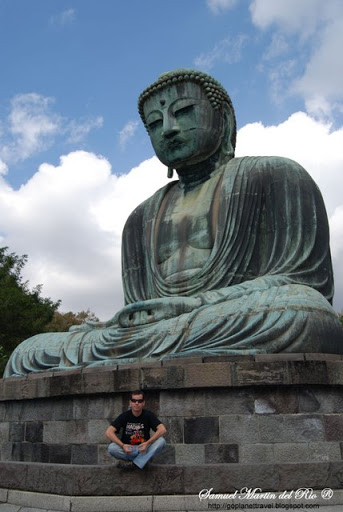

Kamakura is a city located in Kanagawa, Japan, about 50 kilometres (31 mi) south-south-west of Tokyo. It used to be also called Renpu. Although Kamakura proper is today rather small, it is sometimes considered a former de facto capital of Japan as the seat of the Shogunate and of the Regency during the Kamakura Period.

According to The Institute for Research on World-Systems, Kamakura was the 4th largest city in the world in 1250 AD, with 200,000 people, and Japan's largest, eclipsing Kyoto by 1200 AD.

As of January 1, 2008, the city has an estimated population of 1 73,588 and a density of 4,380 inhabitants per square kilometre (11,300 /sq mi). The total area is 39.60 square kilometres (15.29 sq mi).

73,588 and a density of 4,380 inhabitants per square kilometre (11,300 /sq mi). The total area is 39.60 square kilometres (15.29 sq mi).

Kamakura was designated as a city on November 3, 1939.

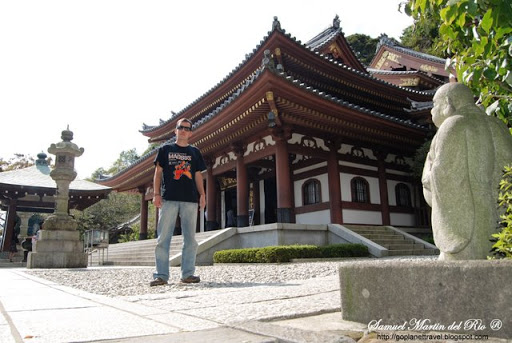

Kamakura has a beach which, in combination with the temples and the proximity to Tokyo, makes it a popular tourist destination. Kamakura's bay has a surf break off of the headland point, albeit an inconsistent one, which makes it at least a second-tier destination for surfers. It is also noted for its senbei, which are crisp rice cakes grilled and sold fresh along the main shopping street. These are very popular with tourists.

The earliest traces of human settlements in the area date back at least 10,000 years. Obsidian and stone tools found at excavation sites near Jōraku-ji were dated to the Old Stone Age (between 100,000 and 10,000 years ago). During the Jōmon period, the sea level was higher than now and all the flat land in Kamakura up to Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū and, further east, up to Yokohama's Totsuka-ku and Sakae-ku was under water. Thus, the oldest pottery fragments found come from hillside settlements of the period between 7500 BC and 5000 BC. In the late Jōmon period the sea receded and civilization progressed. During the Yayoi period (300 BC–300 AD), the sea receded further almost to today's coastline, and the economy shifted radically from hunting and fishing to farming.

The Azuma Kagami describes pre-shogunate Kamakura as a remote, forlorn place, but there is reason to believe its writers simply wanted to give the impression that prosperity was brought there by the new regime. To the contrary, it is known that by the Nara Period (about 700 AD) there were both temples and shrines. Sugimoto-dera was built during this period and is therefore one of the city's oldest temples. The town was also the seat of areal government offices and the point of convergence of several land and marine routes. It seems therefore only natural that it should have been a city of a certain importance, likely to attract Yoritomo's attention.

writers simply wanted to give the impression that prosperity was brought there by the new regime. To the contrary, it is known that by the Nara Period (about 700 AD) there were both temples and shrines. Sugimoto-dera was built during this period and is therefore one of the city's oldest temples. The town was also the seat of areal government offices and the point of convergence of several land and marine routes. It seems therefore only natural that it should have been a city of a certain importance, likely to attract Yoritomo's attention.

There are various hypotheses about the origin of its name. According to the most likely one Kamakura, surrounded as it is on three sides by mountains, was likened both to a cooking stove and to a warehouse , because both only have one side open. It seems therefore likely that it was called at first Kamadokura, and that the syllable do was then gradually dropped.

and to a warehouse , because both only have one side open. It seems therefore likely that it was called at first Kamadokura, and that the syllable do was then gradually dropped.

Another and more picturesque explanation is a legend according to which Fujiwara no Kamatari stopped at Yuigahama on his way to today's Ibaraki Prefecture where he wanted to pray for peace at the Kashima Jingu Shrine. He dreamed of an old man who promised his support, and the day after he found next to his bed a type of sword called kamayari. Kamatari enshrined it in a place called Okura. Kamayari plus Okura turned into Kamaku ra.

ra.

The name appears in the Kojiki of 712. Kamakura is also mentioned in the c. 8th century Man'yōshū as well as in the Wamyō Ruijushō of 938. However, the city clearly appears in the historical record only with Minamoto no Yoritomo and his shogunate of 1192.

The extraordinary events, the historical characters, and the culture of the century that goes from Minamoto no Yoritomo's birth to the assassination of the last of his sons have been throughout Japanese history the background and the inspiration for countless poems, books, jidaigeki TV dramas, Kabuki plays, songs, manga and even videogames, and are necessary to make sense of much of what one sees in today's Kamakura.

Yoritomo, after the defeat and almost complete extermination of his family at the hands of the Taira clan, managed in the space of a few years to go from being a fugitive hiding from his enemies inside a tree trunk to being the most powerful man in the land. Defeating the Taira clan, Yoritomo became de facto ruler of much of Japan and founder of the Kamakura shogunate, an institution destined to last 141 years and to have immense repercussions over the country's history.

Yoritomo, after the defeat and almost complete extermination of his family at the hands of the Taira clan, managed in the space of a few years to go from being a fugitive hiding from his enemies inside a tree trunk to being the most powerful man in the land. Defeating the Taira clan, Yoritomo became de facto ruler of much of Japan and founder of the Kamakura shogunate, an institution destined to last 141 years and to have immense repercussions over the country's history.

The Kamakura shogunate era is called by historians the Kamakura period and, although its end is clearly set (Siege of Kamakura (1333)), its beginning is not: different historians put it at a different point in time within a range that goes from the establishmen t of Yoritomo's first military government in Kamakura (1180) to his elevation to the rank of Seii Taishogun in 1192. It used to be thought that during this period effective power had moved completely from the Emperor in Kyōto to Yoritomo in Kamakura, but the progress of research has revealed this wasn't the case. Even after the consolidation of the shogunate's power in the east, the Emperor continued to rule the country, particularly its west. However, it's undeniable that Kamakura had a certain autonomy and that it had surpassed the technical capital of Japan politically, culturally and economically. The shogunate even reserved for itself an area in Kyōto called Rokuhara where lived its representatives, who were there to protect its interests.

t of Yoritomo's first military government in Kamakura (1180) to his elevation to the rank of Seii Taishogun in 1192. It used to be thought that during this period effective power had moved completely from the Emperor in Kyōto to Yoritomo in Kamakura, but the progress of research has revealed this wasn't the case. Even after the consolidation of the shogunate's power in the east, the Emperor continued to rule the country, particularly its west. However, it's undeniable that Kamakura had a certain autonomy and that it had surpassed the technical capital of Japan politically, culturally and economically. The shogunate even reserved for itself an area in Kyōto called Rokuhara where lived its representatives, who were there to protect its interests.

In 1179 Yoritomo married Hōjō Masako, an event of far-reaching consequences for Japan, and in 1180 he entered Kamakura, building his residence in a valley called Ōkura. The stele on the spot reads:

1180 he entered Kamakura, building his residence in a valley called Ōkura. The stele on the spot reads:

820 years ago, in 1180, Minamoto no Yoritomo built his mansion here. Consolidated his power, he later ruled from home, and his government was therefore called Ōkura Bakufu . He was succeeded by his sons Yoriie and Sanetomo, and this place remained the seat of the government for 46 years until 1225, when his wife Hōjō Masako died. It was then transferred to Utsunomiya Tsuji .

Erected in March 1917 by the Kamakurachō Seinendan

In 1185 his forces, commanded by his younger brother Minamoto no Yoshitsune, vanquished the Taira and in 1192 he received from Emperor Go-Toba the title of Seii Tai Shogun. The Minamoto dynasty and its power however ended as quickly and unexpectedly as they had started.

Tai Shogun. The Minamoto dynasty and its power however ended as quickly and unexpectedly as they had started.

In 1199 Yoritomo died falling from his horse when he was only 51 and was succeeded by his 17-year-old son and second shogun, Minamoto no Yoriie. A long and bitter fight ensued in which entire clans like the Hatakeyama, the Hiki, and the Wada were wiped out by the Hōjō to consolidate their power. Yoriie did become head of the Minamoto clan and was regularly appointed shogun in 1202 but, by that time, real power had already fallen into the hands of his grandfather Hōjō Tokimasa and of his mother. Yoriie plotted to take power back from the Hōjō clan, but failed and was assassinated on July 17, 1204. His six-year-old first son Ichiman had already been killed during political turmoil in Kamakura, while his second son Yoshinari at age six was forced to become a Buddhist priest under the name Kugyō. From then on all power would belong to the Hōjō, and the shogun would be just a figurehead. Since the Hōjō were part of the Taira clan, it can be said that the Taira had lost a battle, but in the end had won the war.

during political turmoil in Kamakura, while his second son Yoshinari at age six was forced to become a Buddhist priest under the name Kugyō. From then on all power would belong to the Hōjō, and the shogun would be just a figurehead. Since the Hōjō were part of the Taira clan, it can be said that the Taira had lost a battle, but in the end had won the war.

Yoritomo's second son and third shogun Minamoto no Sanetomo spent most of his life staying out of politics and writing good poetry, but was nonetheless famously assassinated in February 1219 by his nephew Kugyō under the giant ginkgo tree that still stands at Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū. Kugyō himself, the last of his line, was beheaded as a punishment for his crime by the Hōjō just hours later. Barely 30 years into the shogunate, the Seiwa Genji dynasty who had created it in Kamakura had tragically ended.

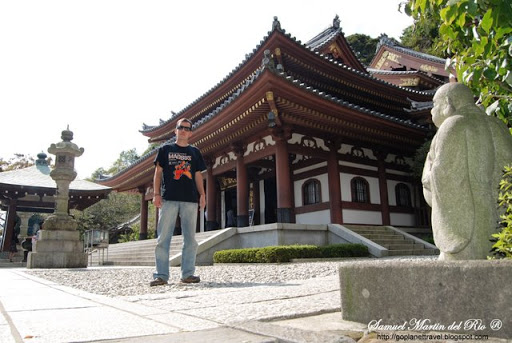

The Hōjō regency, a unique episode in Japanese history, however continued until Nitta Yoshisada destroyed it in 1333 at the Siege of Kamakura. It was under the regency that Kamakura acquired many of its best and most prestigious temples and shrines, for example Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū, Kenchō-ji, Engaku-ji, Jufuku-ji, Jōchi-ji, and Zeniarai Benten Shrine. The Hōjō family crest in the city is therefore still ubiquitous.

From the middle of the thirteenth century, the fact that the vassals (the gokenin) were allowed to become de facto owners of the land they administered, coupled to the custom that all gokenin children could inherit, led to the parcelization of the land and to a consequent weakening of the shogunate. This, and not lack of legitimacy, was the primary cause of the Hōjō's fall.

The fall of Kamakura marks the beginning of an era in Japanese history characterized by chaos and violence called the Muromachi period. Kamakura's decline was slow, and in fact the next phase of its history, in which, as the capital of the Kantō region, it dominated the east of the country, lasted almost as long as the shogunate had. Kamakura would come out of it almost completely destroyed.

The situation in the Kantō after 1333 continued to be tense, with Hōjō supporters staging sporadic revolts here and there. In 1335 Hōjō Tokiyuki, son of last regent Takatoki, tried to re-establish the shogunate by force and defeated Kamakura's de-facto ruler Ashikaga Tadayoshi in Musashi, in today's Kanagawa prefecture. He was in his turn defeated in Koshigoe by Ashikaga Takauji, who had come in force from Kyoto to help his brother.

Takauji, founder of the Ashikaga shogunate which, at least nominally, ruled Japan during the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, at first established his residence at the same site in Kamakura where Yoritomo's Ōkura Bakufu had been, but in 1336 he left Kamakura in charge of his son Yoshiakira and went west in pursuit of Nitta Yoshisada. The Ashikaga then decided to permanently stay in Kyoto, making Kamakura instead the capital of the Kamakura-fu, a region including the provinces of Sagami, Musashi, Awa, Kazusa, Shimōsa, Hitachi, Kozuke, Shimotsuke, Kai, and Izu, to which were later added Mutsu and Dewa, making it the equivalent to today's Kanto, plus the Shizuoka and Yamanashi prefectures.

After the Meiji restoration Kamakura's great cultural assets, its beach and the mystique that surrounded its name made it as popular as it is now, and for pretty much the same reasons. The destruction of its heritage nonetheless didn't stop: during the anti-buddhist violence of 1868 (haibutsu kishaku) that followed the official policy of separation of Shinto and Buddhism (shinbutsu bunri) many of the city temples were damaged. In other cases, because mixing the two religions was now forbidden, shrines or temples had to give away some of their treasures, thus damaging their cultural heritage and decreasing the value of their properties. The shrine also had to destroy Buddhism-related buildings, for example its tahōtō tower, its midō , and its shichidō garan. Some Buddhist temples were simply closed, like Zenkō-ji, to which the now-independent Meigetsu-in used to belong.

In 1890 the railroad, which until then had arrived just to Ofuna, reached Kamakura bringing in tourists and new residents, and with them a ne w prosperity. Part of the ancient Dankazura (see above) was removed to let the railway system's new Yokosuka Line pass.

w prosperity. Part of the ancient Dankazura (see above) was removed to let the railway system's new Yokosuka Line pass.

The volcanic eruption of Sakurajima in January 1914, covered the city in ashes. Lava flows connected the mainland with what had been a small island in the bay.

The damage caused by time, centuries of neglect, politics, and modernization was further compounded by nature in 1923. The epicenter of the Great Kantō earthquake that year was deep beneath Izu Ōshima Island in Sagami Bay, a short distance from Kamakura. Tremors devastated Tokyo, the port city of Yokohama, and the surrounding prefectures of Chiba, Kanagawa, and Shizuoka, causing widespread damage throughout the Kantō region. It was r eported that the sea receded at an unprecedented velocity, and then waves rushed back towards the shore in a great wall of water over seven meters high, drowning some and crushing others beneath an avalanche of water-born debris. The total death toll from earthquake, tsunami, and fire exceeded 2,000 victims. Large sections of the shore simply slid into the sea; and the beach area near Kamakura was raised up about six-feet; or in other words, where there had only been a narrow strip of sand along the sea, a wide expanse of sand was fully exposed above the waterline.

eported that the sea receded at an unprecedented velocity, and then waves rushed back towards the shore in a great wall of water over seven meters high, drowning some and crushing others beneath an avalanche of water-born debris. The total death toll from earthquake, tsunami, and fire exceeded 2,000 victims. Large sections of the shore simply slid into the sea; and the beach area near Kamakura was raised up about six-feet; or in other words, where there had only been a narrow strip of sand along the sea, a wide expanse of sand was fully exposed above the waterline.

Many temples founded centuries ago are just careful replicas, and it's for this reason that Kamakura has just one National Treasure building (the Shariden at Engaku-ji). Much of Kamakura's heritage was for various reasons first lost and later rebuilt.

October 2009

Kamakura is a city located in Kanagawa, Japan, about 50 kilometres (31 mi) south-south-west of Tokyo. It used to be also called Renpu. Although Kamakura proper is today rather small, it is sometimes considered a former de facto capital of Japan as the seat of the Shogunate and of the Regency during the Kamakura Period.

According to The Institute for Research on World-Systems, Kamakura was the 4th largest city in the world in 1250 AD, with 200,000 people, and Japan's largest, eclipsing Kyoto by 1200 AD.

As of January 1, 2008, the city has an estimated population of 1

73,588 and a density of 4,380 inhabitants per square kilometre (11,300 /sq mi). The total area is 39.60 square kilometres (15.29 sq mi).

73,588 and a density of 4,380 inhabitants per square kilometre (11,300 /sq mi). The total area is 39.60 square kilometres (15.29 sq mi).Kamakura was designated as a city on November 3, 1939.

Kamakura has a beach which, in combination with the temples and the proximity to Tokyo, makes it a popular tourist destination. Kamakura's bay has a surf break off of the headland point, albeit an inconsistent one, which makes it at least a second-tier destination for surfers. It is also noted for its senbei, which are crisp rice cakes grilled and sold fresh along the main shopping street. These are very popular with tourists.

The earliest traces of human settlements in the area date back at least 10,000 years. Obsidian and stone tools found at excavation sites near Jōraku-ji were dated to the Old Stone Age (between 100,000 and 10,000 years ago). During the Jōmon period, the sea level was higher than now and all the flat land in Kamakura up to Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū and, further east, up to Yokohama's Totsuka-ku and Sakae-ku was under water. Thus, the oldest pottery fragments found come from hillside settlements of the period between 7500 BC and 5000 BC. In the late Jōmon period the sea receded and civilization progressed. During the Yayoi period (300 BC–300 AD), the sea receded further almost to today's coastline, and the economy shifted radically from hunting and fishing to farming.

The Azuma Kagami describes pre-shogunate Kamakura as a remote, forlorn place, but there is reason to believe its

writers simply wanted to give the impression that prosperity was brought there by the new regime. To the contrary, it is known that by the Nara Period (about 700 AD) there were both temples and shrines. Sugimoto-dera was built during this period and is therefore one of the city's oldest temples. The town was also the seat of areal government offices and the point of convergence of several land and marine routes. It seems therefore only natural that it should have been a city of a certain importance, likely to attract Yoritomo's attention.

writers simply wanted to give the impression that prosperity was brought there by the new regime. To the contrary, it is known that by the Nara Period (about 700 AD) there were both temples and shrines. Sugimoto-dera was built during this period and is therefore one of the city's oldest temples. The town was also the seat of areal government offices and the point of convergence of several land and marine routes. It seems therefore only natural that it should have been a city of a certain importance, likely to attract Yoritomo's attention.There are various hypotheses about the origin of its name. According to the most likely one Kamakura, surrounded as it is on three sides by mountains, was likened both to a cooking stove

and to a warehouse , because both only have one side open. It seems therefore likely that it was called at first Kamadokura, and that the syllable do was then gradually dropped.

and to a warehouse , because both only have one side open. It seems therefore likely that it was called at first Kamadokura, and that the syllable do was then gradually dropped.Another and more picturesque explanation is a legend according to which Fujiwara no Kamatari stopped at Yuigahama on his way to today's Ibaraki Prefecture where he wanted to pray for peace at the Kashima Jingu Shrine. He dreamed of an old man who promised his support, and the day after he found next to his bed a type of sword called kamayari. Kamatari enshrined it in a place called Okura. Kamayari plus Okura turned into Kamaku

ra.

ra.The name appears in the Kojiki of 712. Kamakura is also mentioned in the c. 8th century Man'yōshū as well as in the Wamyō Ruijushō of 938. However, the city clearly appears in the historical record only with Minamoto no Yoritomo and his shogunate of 1192.

The extraordinary events, the historical characters, and the culture of the century that goes from Minamoto no Yoritomo's birth to the assassination of the last of his sons have been throughout Japanese history the background and the inspiration for countless poems, books, jidaigeki TV dramas, Kabuki plays, songs, manga and even videogames, and are necessary to make sense of much of what one sees in today's Kamakura.

Yoritomo, after the defeat and almost complete extermination of his family at the hands of the Taira clan, managed in the space of a few years to go from being a fugitive hiding from his enemies inside a tree trunk to being the most powerful man in the land. Defeating the Taira clan, Yoritomo became de facto ruler of much of Japan and founder of the Kamakura shogunate, an institution destined to last 141 years and to have immense repercussions over the country's history.

Yoritomo, after the defeat and almost complete extermination of his family at the hands of the Taira clan, managed in the space of a few years to go from being a fugitive hiding from his enemies inside a tree trunk to being the most powerful man in the land. Defeating the Taira clan, Yoritomo became de facto ruler of much of Japan and founder of the Kamakura shogunate, an institution destined to last 141 years and to have immense repercussions over the country's history.The Kamakura shogunate era is called by historians the Kamakura period and, although its end is clearly set (Siege of Kamakura (1333)), its beginning is not: different historians put it at a different point in time within a range that goes from the establishmen

t of Yoritomo's first military government in Kamakura (1180) to his elevation to the rank of Seii Taishogun in 1192. It used to be thought that during this period effective power had moved completely from the Emperor in Kyōto to Yoritomo in Kamakura, but the progress of research has revealed this wasn't the case. Even after the consolidation of the shogunate's power in the east, the Emperor continued to rule the country, particularly its west. However, it's undeniable that Kamakura had a certain autonomy and that it had surpassed the technical capital of Japan politically, culturally and economically. The shogunate even reserved for itself an area in Kyōto called Rokuhara where lived its representatives, who were there to protect its interests.

t of Yoritomo's first military government in Kamakura (1180) to his elevation to the rank of Seii Taishogun in 1192. It used to be thought that during this period effective power had moved completely from the Emperor in Kyōto to Yoritomo in Kamakura, but the progress of research has revealed this wasn't the case. Even after the consolidation of the shogunate's power in the east, the Emperor continued to rule the country, particularly its west. However, it's undeniable that Kamakura had a certain autonomy and that it had surpassed the technical capital of Japan politically, culturally and economically. The shogunate even reserved for itself an area in Kyōto called Rokuhara where lived its representatives, who were there to protect its interests.In 1179 Yoritomo married Hōjō Masako, an event of far-reaching consequences for Japan, and in

1180 he entered Kamakura, building his residence in a valley called Ōkura. The stele on the spot reads:

1180 he entered Kamakura, building his residence in a valley called Ōkura. The stele on the spot reads:820 years ago, in 1180, Minamoto no Yoritomo built his mansion here. Consolidated his power, he later ruled from home, and his government was therefore called Ōkura Bakufu . He was succeeded by his sons Yoriie and Sanetomo, and this place remained the seat of the government for 46 years until 1225, when his wife Hōjō Masako died. It was then transferred to Utsunomiya Tsuji .

Erected in March 1917 by the Kamakurachō Seinendan

In 1185 his forces, commanded by his younger brother Minamoto no Yoshitsune, vanquished the Taira and in 1192 he received from Emperor Go-Toba the title of Seii

Tai Shogun. The Minamoto dynasty and its power however ended as quickly and unexpectedly as they had started.

Tai Shogun. The Minamoto dynasty and its power however ended as quickly and unexpectedly as they had started.In 1199 Yoritomo died falling from his horse when he was only 51 and was succeeded by his 17-year-old son and second shogun, Minamoto no Yoriie. A long and bitter fight ensued in which entire clans like the Hatakeyama, the Hiki, and the Wada were wiped out by the Hōjō to consolidate their power. Yoriie did become head of the Minamoto clan and was regularly appointed shogun in 1202 but, by that time, real power had already fallen into the hands of his grandfather Hōjō Tokimasa and of his mother. Yoriie plotted to take power back from the Hōjō clan, but failed and was assassinated on July 17, 1204. His six-year-old first son Ichiman had already been killed

during political turmoil in Kamakura, while his second son Yoshinari at age six was forced to become a Buddhist priest under the name Kugyō. From then on all power would belong to the Hōjō, and the shogun would be just a figurehead. Since the Hōjō were part of the Taira clan, it can be said that the Taira had lost a battle, but in the end had won the war.

during political turmoil in Kamakura, while his second son Yoshinari at age six was forced to become a Buddhist priest under the name Kugyō. From then on all power would belong to the Hōjō, and the shogun would be just a figurehead. Since the Hōjō were part of the Taira clan, it can be said that the Taira had lost a battle, but in the end had won the war.Yoritomo's second son and third shogun Minamoto no Sanetomo spent most of his life staying out of politics and writing good poetry, but was nonetheless famously assassinated in February 1219 by his nephew Kugyō under the giant ginkgo tree that still stands at Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū. Kugyō himself, the last of his line, was beheaded as a punishment for his crime by the Hōjō just hours later. Barely 30 years into the shogunate, the Seiwa Genji dynasty who had created it in Kamakura had tragically ended.

The Hōjō regency, a unique episode in Japanese history, however continued until Nitta Yoshisada destroyed it in 1333 at the Siege of Kamakura. It was under the regency that Kamakura acquired many of its best and most prestigious temples and shrines, for example Tsurugaoka Hachiman-gū, Kenchō-ji, Engaku-ji, Jufuku-ji, Jōchi-ji, and Zeniarai Benten Shrine. The Hōjō family crest in the city is therefore still ubiquitous.

From the middle of the thirteenth century, the fact that the vassals (the gokenin) were allowed to become de facto owners of the land they administered, coupled to the custom that all gokenin children could inherit, led to the parcelization of the land and to a consequent weakening of the shogunate. This, and not lack of legitimacy, was the primary cause of the Hōjō's fall.

The fall of Kamakura marks the beginning of an era in Japanese history characterized by chaos and violence called the Muromachi period. Kamakura's decline was slow, and in fact the next phase of its history, in which, as the capital of the Kantō region, it dominated the east of the country, lasted almost as long as the shogunate had. Kamakura would come out of it almost completely destroyed.

The situation in the Kantō after 1333 continued to be tense, with Hōjō supporters staging sporadic revolts here and there. In 1335 Hōjō Tokiyuki, son of last regent Takatoki, tried to re-establish the shogunate by force and defeated Kamakura's de-facto ruler Ashikaga Tadayoshi in Musashi, in today's Kanagawa prefecture. He was in his turn defeated in Koshigoe by Ashikaga Takauji, who had come in force from Kyoto to help his brother.

Takauji, founder of the Ashikaga shogunate which, at least nominally, ruled Japan during the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries, at first established his residence at the same site in Kamakura where Yoritomo's Ōkura Bakufu had been, but in 1336 he left Kamakura in charge of his son Yoshiakira and went west in pursuit of Nitta Yoshisada. The Ashikaga then decided to permanently stay in Kyoto, making Kamakura instead the capital of the Kamakura-fu, a region including the provinces of Sagami, Musashi, Awa, Kazusa, Shimōsa, Hitachi, Kozuke, Shimotsuke, Kai, and Izu, to which were later added Mutsu and Dewa, making it the equivalent to today's Kanto, plus the Shizuoka and Yamanashi prefectures.

After the Meiji restoration Kamakura's great cultural assets, its beach and the mystique that surrounded its name made it as popular as it is now, and for pretty much the same reasons. The destruction of its heritage nonetheless didn't stop: during the anti-buddhist violence of 1868 (haibutsu kishaku) that followed the official policy of separation of Shinto and Buddhism (shinbutsu bunri) many of the city temples were damaged. In other cases, because mixing the two religions was now forbidden, shrines or temples had to give away some of their treasures, thus damaging their cultural heritage and decreasing the value of their properties. The shrine also had to destroy Buddhism-related buildings, for example its tahōtō tower, its midō , and its shichidō garan. Some Buddhist temples were simply closed, like Zenkō-ji, to which the now-independent Meigetsu-in used to belong.

In 1890 the railroad, which until then had arrived just to Ofuna, reached Kamakura bringing in tourists and new residents, and with them a ne

w prosperity. Part of the ancient Dankazura (see above) was removed to let the railway system's new Yokosuka Line pass.

w prosperity. Part of the ancient Dankazura (see above) was removed to let the railway system's new Yokosuka Line pass.The volcanic eruption of Sakurajima in January 1914, covered the city in ashes. Lava flows connected the mainland with what had been a small island in the bay.

The damage caused by time, centuries of neglect, politics, and modernization was further compounded by nature in 1923. The epicenter of the Great Kantō earthquake that year was deep beneath Izu Ōshima Island in Sagami Bay, a short distance from Kamakura. Tremors devastated Tokyo, the port city of Yokohama, and the surrounding prefectures of Chiba, Kanagawa, and Shizuoka, causing widespread damage throughout the Kantō region. It was r

eported that the sea receded at an unprecedented velocity, and then waves rushed back towards the shore in a great wall of water over seven meters high, drowning some and crushing others beneath an avalanche of water-born debris. The total death toll from earthquake, tsunami, and fire exceeded 2,000 victims. Large sections of the shore simply slid into the sea; and the beach area near Kamakura was raised up about six-feet; or in other words, where there had only been a narrow strip of sand along the sea, a wide expanse of sand was fully exposed above the waterline.

eported that the sea receded at an unprecedented velocity, and then waves rushed back towards the shore in a great wall of water over seven meters high, drowning some and crushing others beneath an avalanche of water-born debris. The total death toll from earthquake, tsunami, and fire exceeded 2,000 victims. Large sections of the shore simply slid into the sea; and the beach area near Kamakura was raised up about six-feet; or in other words, where there had only been a narrow strip of sand along the sea, a wide expanse of sand was fully exposed above the waterline.Many temples founded centuries ago are just careful replicas, and it's for this reason that Kamakura has just one National Treasure building (the Shariden at Engaku-ji). Much of Kamakura's heritage was for various reasons first lost and later rebuilt.

October 2009

You have read this article with the title KAMAKURA, JAPAN. You can bookmark this page URL https://tiogatalk.blogspot.com/2009/10/kamakura-japan.html. Thanks!

Write by:

AN - Thursday, October 29, 2009

Comments "KAMAKURA, JAPAN"

Post a Comment